The main category of Fitness News.

You can use the search box below to find what you need.

[wd_asp id=1]

The main category of Fitness News.

You can use the search box below to find what you need.

[wd_asp id=1]

Flag Football gained popularity in Mexico, and instrumental in this rise is the member of Mexico’s women’s team, Silvia Contreras, who has led her squad to win both gold and silver at the World Games. She started playing Flag Football in high school when a friend of her who was a big fan of American football wanted to try it out. She went with her to see what it was all about, and fell in love with it in 2009. She made it to the national team in 2018, and in 2022 she became the captain and later during the IFAF Americas Championship, she was named officially the captain of the Mexico national Flag Football team.

As part of the Mexico Flag Football women’s team who has been TWG Champions from 2022 in Birmingham, Alabama, and won the silver medal at the 2024 World Championships in Lahti, Finland.

Gold Medal TWG 2022 BHM Alabama

Silver Medal FFWC 2021 Jerusalem Israel

National Champ 2022 Mexico City

National Champ 2022 Mexico City and Most Valued Player

Gold Medal The World Games 2022

Silver Medal IFAF World Championship 2021 and 2024

Women Fitness President Ms. Namita Nayyar catches up with Silvia Contreras is an exceptionally talented Mexican Flag Football Player, winner of gold medal at The World Games 2022, here she talks about her fitness routine, her diet, and her success story.

Where were you born? You in 2009 started playing Flag Football while in high school. You were selected in the Mexican Flag Football team in 2018 and went on to become its captain in 2022. This later propelled your career to the height where you have been at the top of the world as a Flag Football player. Tell us more about your professional journey of exceptional hard work, tenacity, and endurance?

I was born in Ciudad Obregón, Sonora, México a very small town but when I was three years old my family moved to Tijuana, a big city just across the border from San Diego.

Well I think most if not everything that I have accomplished it’s because of two main things, passion (the love that I have for this game) and discipline. When I started playing I had no idea of anything about this sport, I’ve always loved and practiced sports but not this one in particular so it was a pretty tough challenge.

At first I wasn’t that good but I enjoyed it and loved the way I could see that I was getting better through training, that’s when I fell in love with the process, not just the results. Now I can say that is what put me here and that is why I can continue doing this at the highest level and with so many sacrifices but enjoying it all the way. The support of my family has been so important also, because when I started in the national team I was already graduated, working and supposed to be entering my “normal” adult life, but they know how much I love this and the big dreams that I had so they let me chase my dreams and supported me all the way,

It is a dream for a Flag Football player to play in the Flag Football World Games. You won a Gold medal being part of the Mexican Team at the 2022 World Games that took place in July 2022, in Birmingham, Alabama in the United States.Tell us more about this spectacular achievement of yours?

Well, I feel lucky because I am living what I believe is the best moment for a flag football player, I’ve been playing this sport for 15 years and at the beginning not even me knew what this sports was about, now we have to opportunity to dream with something like The World Games and the Olympics but that was not a dream that we could ever imagined we could have in 2009. So it’s been a rollercoaster that just goes up and up for me towards dreaming.

When we heard that we´ve been invited to the world Games that was a huge achievement for the sport and the fact that TWG were going to be so important for the sport to be accepted to the Olympics put some pressure on it, but my dreams have always been big so I just got to work, individually and with my team, That gold medal was totally TEAMWORK and TEAM effort in every aspect, from our staff to the players, even the country, families and fans. It was a total dream, we enjoyed every second and I think people could see it through the screen. We put so much work, time, money, and sacrifices towards this goal and that made it extra special.

The 2021 IFAF Women’s Flag Football World Championships was the 10th World Championships in women’s flag football. The tournament took place in Jerusalem, Israel, from 6 to 8 December 2021. Representing the Mexican Team you won a silver medal. How does such winning honor being bestowed upon you act as a catalyst in your metriotic rise as a world leading Flag Football player?

That tournament was definitely very important for me as an athlete mentally because that was my second time representing Mexico on a World Championship but the first time I did badly. I was considering not coming back to try again because it was a very tough challenge for me to get over that moment and my performance. So the 3 years that went by since my first to Israel I put so much effort in every aspect I went from being just a flag football player to becoming an athlete and that help me so much with my confidence and also my performance in the field. I enjoyed the 2021

Worlds and I know a silver medal it’s a huge achievement but I wasn’t satisfied because I knew we could have had the gold medal, so the next months were crucial and we got it. Also it was from moment that I assume a role in the Mexican national team that I don’t want to give up, my position, experience and my story has been inspiring others to try and be here to so I´ve been sharing my thoughts and my process with others to see if I can help or if my road can help someone else to also achieve this dreams.

Full Interview is Continued on Next Page

This interview is exclusive and taken by Namita Nayyar President of womenfitness.net and should not be reproduced, copied, or hosted in part or full anywhere without express permission.

All Written Content Copyright © 2025 Women Fitness

Disclaimer

The Content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition.

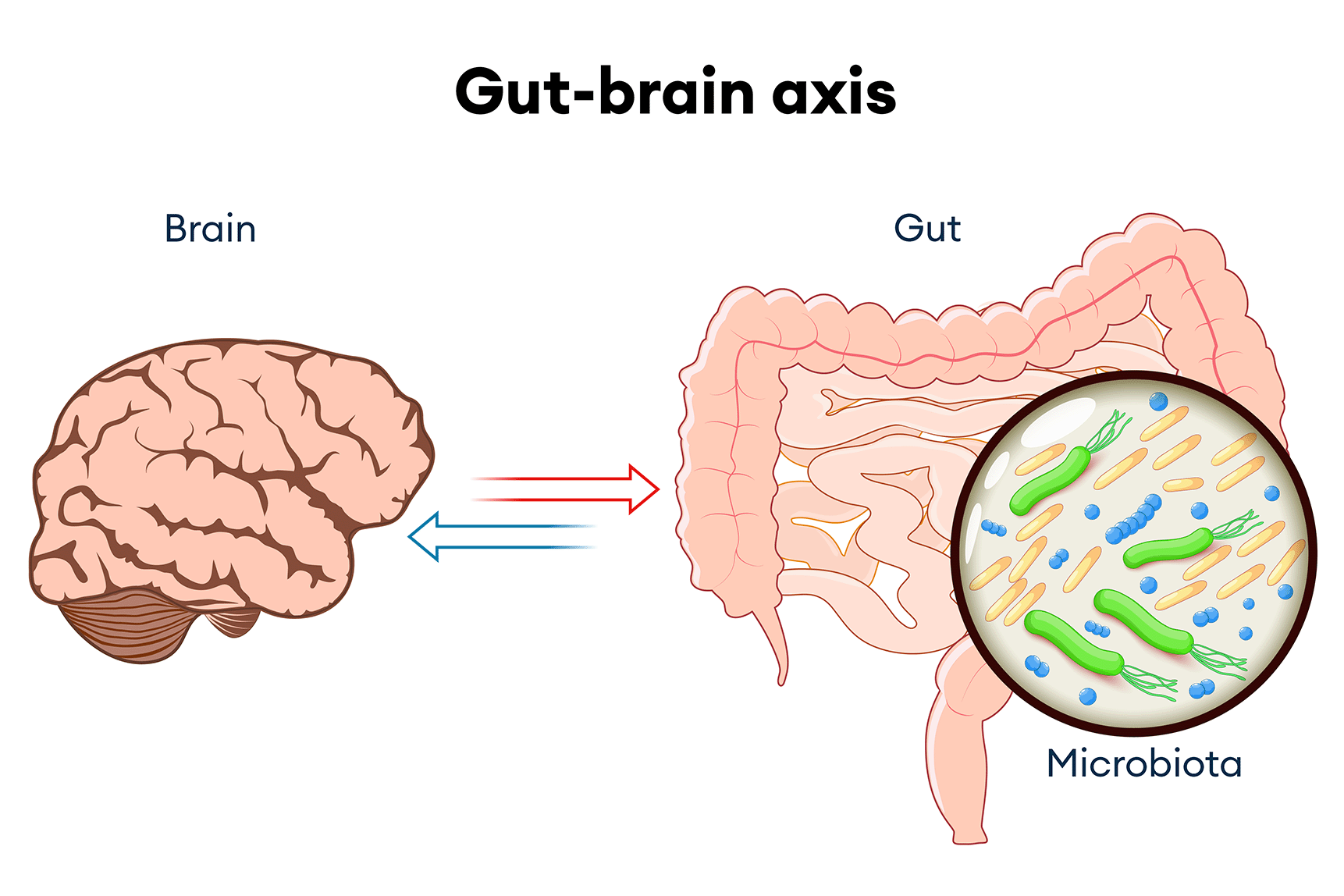

Emerging research highlights the significant role of blueberries in modulating the gut-brain axis, thereby influencing both gastrointestinal and cognitive health. The gut-brain axis is the bidirectional communication network connecting the gastrointestinal tract and the brain, involving neural, hormonal, and immunological pathways.

Blueberries are rich in anthocyanins and other polyphenols, which possess prebiotic properties that support a healthy gut microbiome. These compounds can enhance the growth of beneficial bacteria, such as bifidobacteria, and improve intestinal barrier function. A systematic review of animal studies indicated that blueberry supplementation improved gut health by enhancing intestinal morphology, reducing gut permeability, suppressing oxidative stress, and modulating gut microbiota composition.

The gut microbiome plays a crucial role in brain health through the production of neurotransmitters and the modulation of inflammation. By promoting a balanced gut microbiota, blueberries may indirectly support cognitive functions. For instance, a study found that daily consumption of wild blueberries led to improved executive function, better short-term memory, and faster reaction times in older adults.

Research suggests that the beneficial effects of blueberries on the gut-brain axis may be mediated through several mechanisms:

Neuroinflammation Reduction:

Blueberry anthocyanins have been shown to decrease neuroinflammation, which is linked to cognitive decline. In a mouse model of autism spectrum disorder, anthocyanin-rich extracts from blueberries alleviated autism-like behaviors and reduced both neuroinflammation and gut inflammation.

Serotonin Production:

Approximately 90% of serotonin, a neurotransmitter that regulates mood, is produced in the gut. Blueberries may influence serotonin levels by promoting a healthy gut microbiome, positively affecting mood and cognitive functions.

Short-Chain Fatty Acid (SCFA) Production:

The fermentation of blueberry fibers by gut bacteria leads to the production of SCFAs, which have anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective properties. This process supports the integrity of the gut barrier and influences brain health.

Incorporating them into the diet may offer a natural approach to enhancing gut health and cognitive function by positively influencing the gut-brain axis.

Disclaimer

The Content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition.

As told to Jacquelyne Froeber

“I’ve never seen anything as invasive as this in my life,” my surgeon said.

I was still groggy from the anesthesia, but the look on his face meant what I heard was true. Apparently, I was in surgery for six hours — not two — and whatever was growing in my ear was also in the layers of tissue protecting my brain.

“It looks like cancer,” he said.

Shock doesn’t even begin to describe what I felt at that moment. I went in for an ear infection. Now I have brain cancer?

It all started innocently enough. In January 2011, my right ear was full of pressure and everything sounded muffled, like I was underwater. But I didn’t think it was too serious. January was actually a really happy and exciting time. It was the month my first granddaughter was born, and I couldn’t think of a better way to start the new year.

I was diagnosed with a mild ear infection, so I took antibiotics but they didn’t help. Nothing did. I was eventually referred to an ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialist, but it took months to get an appointment. When I finally got in to see the specialist, I had a scan of my ear. The imaging showed that there was a mass, so they did a biopsy right away.

It was after the biopsy surgery that I learned that the mass was also in my brain and probably cancerous. But the pathology report came back negative. “How is that possible?” I asked. My provider was stumped. He said the tumors acted like cancer, so we were going to treat it like cancer — very aggressively.

I had surgery to remove the tumors — and that surgery was a success — but six weeks later, the mass was back. And two weeks after that, another mass was growing in the left side of my head. It took five surgeries to remove that one.

We still didn’t have confirmation that the tumors were cancer, but I started radiation to try to stop them from growing. I’m a radiologic technologist by trade, so I understood the effects of radiation treatments — but I didn’t know how terrible the side effects were going to be for me. The treatments left me weak and drained of all my energy. I was also having debilitating headache attacks that felt like a sledgehammer to the skull.

On top of everything, the radiation wasn’t working. And at that point, the mass had damaged the hearing structures in my right ear, and I needed surgery for a cochlear implant.

(Photo/Courtesy of Sabrina Riddle)

By November 2013, I was worn down. Exhausted. Depressed and unable to hear out of my right ear. With my granddaughter’s second birthday approaching, I could only think one thing: I’ve been in this fight for two years and here comes another year I’m going to have to deal with whatever this undiagnosed thing is.

I’d seen many specialists in effort to get a diagnosis and treatment plan. But one particular rheumatologist was curious enough to order a spinal tap. When the results of the spinal tap came in, she said, “I think I know what you have, but I can’t diagnose you. I need you to go to Massachusetts to see the leading researcher for this disease.”

She didn’t have to tell me twice. I packed my bags and met with the specialist the next week. His name was Dr. Stone, and he told me I had immunoglobulin G4-related disease (IgG4-RD) — an extremely rare inflammatory disease. He explained to me that IgG4-RD causes tumors to form in different parts of your body and it looks and behaves just like cancer because it’s so aggressive — but it’s not cancer.

I sobbed with relief right there in his office — I finally had a diagnosis. But I was also crying for the past three years of my life. All of the surgeries, multiple hospitalizations, the boatload of steroids — and they have their own set of issues — none of it helped. I don’t fault the doctors for any of it, but I’d been through a lot. And if that was the treatment for cancer — what would treatment for a rare disease like this one be like?

Dr. Stone is known as the godfather of IgG4-RD, and he reassured me that my new treatment plan was going to work and it wasn’t as harsh as radiation. I started a biologic infusion and right away I began to see signs that the disease was going into remission. It felt like a weight was being lifted off of my life. For the first time in a long time, I felt hope for the future.

I started feeling better — I had way more energy, fewer headache attacks and visual disturbances, and improved joint pain. I even got a little cocky, thinking I was a one-and-done and I could put the disease behind me.

But that wasn’t the case. In 2015, I had a relapse. It started with blurred vision and severe headache attacks — and this time the cognitive decline was swift and shocking. I was devastated. I had the treatment infusion, and within about two months, I started to feel more like myself again. But when I relapsed again in 2017, I realized that this was probably going to be a pattern for the rest of my life.

Each time takes a toll. The effects of IgG4-RD disease on the layers of my brain (called meninges) can cut off oxygen to the brain and arteries and cause seizures, so I am really concerned with each flare because I don’t know what might happen each time it comes back.

Last November, I was on the phone with my sister and I just lost it. I felt like the disease was looming over my life, even when I was in remission. The loneliness that comes with having a rare disease adds another layer of sadness and despair. I didn’t have a single person to talk to who really knew about what was happening to me or understood that I looked OK on the outside, but I was the furthest thing from OK. I told her I wished there were more advocacy around the disease.

About a week later, I got my wish. An advocacy group called me and asked if I’d be interested in speaking at a conference about IgG4-RD. I was so shocked I nearly dropped the phone. By December, I was on a plane to the conference, and since then I’ve been working as a patient advocate for IgG4-RD.

Through my new platform, I connect with other patients with IgG4-RD, as well as caregivers and healthcare providers trying to advance treatment for the disease. Having a community has been a life changer for me. Having a rare disease is exhausting — especially one that affects your brain. But I now know that I don’t walk this road alone.

Right now, I’m going through a relapse and it’s hard. The pain is sometimes unmanageable and the heavy doses of pain medication weigh me down. But in the past year I’ve seen so much advocacy and research that makes me hopeful for the future. And sometimes all you can do is keep hope alive while you wait.

This educational resource was created with support from Amgen, a HealthyWomen Corporate Advisory Council member.

Related Articles Around the Web

My second year of professional soccer started out great. I worked hard during training, and I got stronger and faster every day. Then one afternoon — out of the blue — a tsunami of fatigue washed over me. It was so bad I couldn’t climb the stairs to my second-floor apartment without stopping to rest.

There I was, a professional athlete running miles a day, and I could barely make it up the stairs.

Still, I didn’t think it was anything serious. “It’s mono,” I thought. I’d sleep it off and feel better in a few days. But the fatigue was relentless. By the next week, I could barely move. My legs were so heavy they felt like they were in quicksand. As I stood in the middle of the practice field, it hit me that there was something seriously wrong with my body.

The team trainer told me to see a healthcare provider immediately. That provider ordered blood work, and it turned out, my white blood count was really low.

He referred me to an oncologist, which shook me to my core. I didn’t know much about cancer but that thought hadn’t crossed my mind. Thankfully, when I saw the oncologist the following day, he said I didn’t have cancer, but he wanted me to see a rheumatologist.

I was lucky to get an appointment for the following week, and I continued to play soccer even though I was running on fumes. When I saw the rheumatologist, he said my liver enzymes were really high and he wanted to do a Schirmer’s test. Of course, I didn’t know what that was, but I said yes. He took two innocent-looking strips of paper and stuck them under my eyelids. It was the worst experience ever. Those five minutes felt like five years. When he finally pulled the strips from my eyes, they were completely dry, which meant my tear glands weren’t producing fluid.

“You have Sjögren’s,” he said. He handed me some pamphlets and explained that I had an autoimmune disease that attacked moisture-producing glands in my body and caused dry eyes, dry mouth and bouts of fatigue. In my case, the fatigue was extreme.

And that was it. He pretty much sent me on my way and made it sound like Sjögren’s disease wasn’t a big deal. I’d just have to push through the tiredness until I felt better.

But everything got worse.

On top of the heaviness and fatigue, I started having joint pain and muscle pain on a level I’d never felt before. As an athlete, I was very aware of my body and I knew what I was experiencing wasn’t normal. I wondered if it could be connected to Sjögren’s disease, but in 2002 there wasn’t much information out there. The provider gave me all the resources (pamphlets) he had. Shortly after I was diagnosed, I moved to another city and another team, which is common in soccer and meant I had to start over with a new healthcare provider every six months.

For years, I felt like the only person in the world with Sjögren’s disease. I didn’t know anyone who had it, and I hid my symptoms from teammates and coaches because I was afraid they would think I couldn’t play at the elite level. This wasn’t just paranoia — I told my first coach I had Sjögren’s disease right after I was diagnosed, and I went from starting every game to basically being benched. So I wasn’t taking any chances going forward.

Although I tried to keep the disease a secret, there were physical symptoms I couldn’t hide. Some games, I was literally foaming at the mouth because I don’t make enough saliva and I couldn’t just break for water whenever I wanted.

The mysterious joint and muscle pain never stopped — and I never stopped trying to figure out why it was happening. In 2008, I went to a new provider who ordered some different tests. When the labs came back, she diagnosed me with lupus. She said it made sense because many people with Sjögren’s disease have additional autoimmune diseases, and lupus is a common one.

I was stunned. Two diseases? How much can one person handle? But I was also relieved. For years, I’d been in pain and having joint issues and no one knew why. Now I knew I was dealing with another disease, and I could tackle both head-on.

I told my family about the double diagnosis, but no one else. I continued to push through days I didn’t feel good and played bad and couldn’t express why. And there were many days when the loneliness of keeping it all a secret hurt more than anything else. I won my second Olympic gold medal that year, but it was one of the hardest times in my life.

In 2011, I started volunteering for the Lupus Foundation, and I was so inspired by the research and growing community that I realized I could use my platform to help bring awareness to both lupus and Sjögren’s disease.

I told my coaches first and then my teammates. Everyone said the same thing: “We had no clue.” And everyone was amazing — it makes me emotional when I think of all the kindness and support they gave me right away. One night at dinner, I was having a flare and the joint pain in my wrist and fingers was so bad it was hard for me to cut my steak. My teammate next to me didn’t say a word — she just grabbed my plate, cut up the steak, placed it back down in front of me and continued with her dinner. Later that night, I was struggling to step down from the bus when suddenly I had teammates all around me picking me up and helping me to the ground. No one looked at me differently or treated me differently. I know in my heart that their support was the reason I was able to go on and play for so long.

2024

In 2012, I went public about living with both diseases and won my third (and final) Olympic gold medal. I retired in 2015 and started putting more of my energy into raising awareness about lupus and Sjögren’s disease.

Today the diseases have more of an impact on my life than when I was playing professionally. My eyes are constantly grainy and painful because I don’t make enough fluid to keep them moisturized and clean. I still have a lot of joint pain and, most days, I’m so tired I don’t really remember what it’s like to have a lot of energy. This is my new normal. All of it takes a toll. But I’m thankful there’s a lot of support in the Sjögren’s community. I know we’re all on the same team, striving for advancements in treatments that don’t just help us live our lives. A cure is the goal.

This educational resource was created with support from Amgen, a HealthyWomen Corporate Advisory Council member.

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web

As told to Erica Rimlinger

At my annual physical in spring 2002, my blood work was not quite right. “Your liver function isn’t great,” the doctor said. “We’ll give it another year, and if it’s still off, we’ll do something about it.” I didn’t think much about it. I didn’t have symptoms worth noting. I was tired, of course, but aren’t most people?

The next year, when my blood work again came back looking suspicious, my doctor called and left me a message at work, saying he wanted to test me for hepatitis. I was surprised and more than a little confused: I had no risk factors. I was certain my doctor was wrong.

A few months later, I changed jobs. I had to wait for my new health insurance to begin, and I didn’t have enough sick time to take time off from work to go to the doctor anyway.

But health problems don’t always care about your insurance or sick leave availability. One day at my new job, I had a gastric attack that kept me in the bathroom for 45 minutes. There was so much blood I thought I must have been bleeding internally.

Once I composed myself enough to return to my desk and call my doctor, I had to ask my new, all male coworkers: “Can somebody drive me to the hospital?” Panic ensued. After debating who had the keys, what hospital I was going to, and who was going to call my parents, one coworker screeched his car up to the front of the building and drove me, quickly and sometimes in the wrong direction, to the hospital. I tried to stay calm amid the chaos, but inside, I was panicking.

At the hospital, the tests revealed no clues to the source of the attack. I was instructed to make an appointment with a gastroenterologist, a GI doctor. I saw him the week before Christmas, and he told me he thought I had primary biliary cholangitis, or PBC. As part of the diagnosis, the doctor ordered a liver biopsy to confirm this and said that in his 30 years practicing medicine, he’d only seen one other person with this condition.

What was PBC? My mom and I sat crying in the car outside the doctor’s office, searching the internet on our phones. I read that I could require a liver transplant and that PBC could shorten my lifespan. I didn’t know if I was going to live or for how long. We didn’t tell anybody, except for my husband, until after the holidays. I didn’t want to ruin Christmas.

The biopsy confirmed I had PBC, and I started taking a medicine that would be the only PBC treatment available to me for many years to come.

Some people have symptoms that lead to their PBC diagnosis, but I didn’t. After I was diagnosed, however, I started experiencing severe diarrhea, making my normal daily activities impossible. One memorable occurrence found me crouched under an umbrella in the pouring rain on the side of a highway. With the help of my husband and family, I coped, eventually developing systems and tools to get me through. Hoping to improve my health, I had gastric bypass surgery in 2007, believing — unrealistically — that weight loss would help with all my liver problems. It didn’t.

2022

I stopped investing my energy in wishful thinking and realized I needed to live with my illnesses, not just survive. I started with my upcoming high school reunion. In high school I’d been a wallflower: I didn’t participate in activities and kept to myself. But today I realized that person needed to change. I volunteered to help plan the reunion, and the reunion committee gave out a new award that year: the butterfly award. I won it because I had finally come out of my chrysalis. I knew I was on the right path.

I started advocacy work, which I continue to do today. Every February, I head up to Capitol Hill to advocate for rare diseases. My goal is to knock on every door every year until there are no more rare diseases to cure.

After a while, the PBC medication I’d been taking for many years stopped working as well as it had been, and my blood work started to show that my liver function was getting worse. My gastroenterologist was retiring, but through networking with other people living with PBC, I found a doctor who put me on a new medication that turned out to be a good fit for me.

Then the FDA took some steps that impacted my ability to get the medicine. My newfound advocacy and lobbying skills came to the rescue when I later testified before the FDA on behalf of the medication. After the hearing, the FDA put steps in place that would keep the medicine available. I’d been heard.

My experience with a rare chronic illness has taught me to find something good out of every bad thing. Today, I have hope for new developments that will be coming with improved understanding of the disease. I wish more people with PBC knew they have treatment options. There’s no cure — that’s true — but you can make plans.

You can live a life and be a whole person, not a statistic. I have PBC, but I’m not PBC, and I’m not defeated by it. Dealing with a rare chronic illness has helped me discover a belief in myself I never knew I had.

This educational resource was created with support from Gilead.

Have your own Real Women, Real Stories you want to share?Let us know.

Our Real Women, Real Stories are the authentic experiences of real-life women. The views, opinions and experiences shared in these stories are not endorsed by HealthyWomen and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of HealthyWomen.

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web

February 24 – March 3, 2025, is National Eating Disorders Awareness Week.

Alice* can’t remember a time when she felt comfortable in her body.

Growing up, she developed a lot earlier than the other girls her age, and her school didn’t offer much in the way of education about women’s health. She felt alone, and her cannonball into womanhood made her a target for bullying. In high school, she was relentlessly teased by boys and pushed into lockers by girls who called her “slut.”

Alice thought that if she could just shrink her body — take up less space — maybe it would all go away.

She started restricting calories and the types of food she ate. If she did eat something “bad,” she’d make herself throw up, which helped her feel in control. Alice cycled through periods of restricted eating, binging and purging for years. She told herself that it didn’t rule her life or happen every day, so it wasn’t a problem. But when she got an invite to a class reunion, she realized her “non-problem” had been going on for decades.

For some women like Alice, eating disorders in midlife can be the result of an untreated pattern that started earlier on in life. But there are a lot of different reasons that eating disorders develop or reoccur in midlife.

“When you think about some of the things that we know about eating disorders — they’re biologically based, they often co-occur with other mental health issues — the changes in midlife for women can create new stressors or bring on or exacerbate existing conditions,” said Doreen Marshall, Ph.D., CEO of the National Eating Disorders Association. “For women in midlife, there’s often changes to their bodies that they’re navigating. For many women, it’s years of dealing with fertility or fertility issues or childbirth. It’s also dealing with perimenopause.”

Although many people associate eating disorders with youth, research shows that rates of eating disorders among women in midlife have increased over the years. The statistics are alarming: One study found that 1 in 5 women have dealt with an eating disorder by age 40 — twice the number identified for women at age 21.

More than 1 in 10 women over 50 experience symptoms of an eating disorder, and a recent study found nearly 3 out of 4 women in midlife are not satisfied with their weight, which is a risk factor for developing an eating disorder.

“Disorders do not discriminate based on age, gender, body type, socioeconomic status, race — no one is immune,” Marshall said.

But there are some factors that may increase the risk for developing an eating disorder in midlife. Body changes during perimenopause (the time period leading up to menopause) and menopause can contribute to the risk. Most people start perimenopause in their 40s and during this time, estrogen levels start to decline, which causes your metabolism to slow and can contribute to weight gain.

Marshall said hormonal changes paired with aging in general are all risk factors that come with this stage in life. Other risk factors can include:

“I think what’s clear is that there’s no one cause for an eating disorder, and that eating disorders are complex — they involve biology and environmental stressors or environmental exposure. And we’re all impacted by things like weight loss culture and diet culture and beauty ideals … Coupled with changes in midlife, that can really set someone [with vulnerabilities] up for development of an eating disorder,” Marshall said.

There are many different types of eating disorders, but the three most common eating disorders in midlife are:

Marshall noted that orthorexia, an obsession with healthy eating and restricting food, can also develop during this stage of life. “This is somebody who has a preoccupation with healthy eating to the point where it’s interrupting their ability to function socially, occupationally or just even in the world,” she said.

It may come as a surprise to find out that eating disorders have the second highest death rate of any mental illness. And dealing with an eating disorder in midlife makes you more vulnerable to serious physical health conditions that happen with age.

These can include:

Eating disorders that cause malnutrition can also contribute to cognitive functioning deficiencies For example, studies show that people with anorexia have poor decision-making skills.

For Alice, the realization that she did have a problem prompted her to start seeing a therapist. If you’re not sure if you have an eating disorder, consider taking the National Eating Disorders Association screening tool. It’s free and confidential and can give you information you need to bring to your healthcare provider — preferably one that has experience with treating eating disorders.

“Treatment for eating disorders often involves a mental health professional and it can involve a dietician and a medical doctor. So, I think it’s just important that people reach out and that they start talking to their medical providers,” Marshall said. “These are illnesses that exist in silence and secrecy. And when someone takes a first step toward help, it’s a step toward bringing this into the light.”

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web

When you hear the word “epidemic,” what do you think of? Smallpox? Yellow fever? Polio?

What about loneliness?

It may not seem like feeling lonely could be a serious public health issue, but that’s what makes it so sneaky — and scary. In 2023, the surgeon general called out loneliness for its severe impact on mental and physical health, comparing social disconnect to smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

And because loneliness is more subjective than, say, smoking or smallpox, recognizing and treating it can be complicated.

“If you want to know if someone is lonely, they have to tell you,” said Jeremy Nobel, M.D., MPH, founder and president of The Foundation for Art & Healing, a nonprofit that helps people find resources to combat loneliness. For perspective, Nobel said to pretend you have the universe’s most powerful telescope that can see through walls and you are on the moon. “You could see all the isolated people on planet Earth, but you couldn’t figure out who was lonely.”

Loneliness is the feeling of being alone, or that you don’t have meaningful, close relationships or a sense of belonging, regardless of how much social contact you have.

Ironically, there are a lot of people who feel this way. In fact, a 2024 survey by the American Psychological Association found 1 in 3 adults experience feelings of loneliness at least once a week.

And loneliness isn’t just a problem in the U.S. About 1 in 4 people worldwide — more than a billion people — feel “fairly” or “very” lonely, according to a recent survey of more than 140 countries. The survey also found that, in more than half of those countries, more women feel lonely than men.

Chronic loneliness is more complex than just an occasional feeling — which everyone has, by the way. It’s perfectly natural to feel lonely from time to time. But long-term, or chronic, loneliness increases your risk for certain physical and mental health conditions, including depression.

Read: Is It Just Sadness or Is It Clinical Depression? >>

Nobel said loneliness is like a pyramid. The bottom tier includes everyone because we all experience loneliness at some point. The middle tier is when you’re going through a challenge — perhaps a break-up or you’re taking care of a child or a parent with an illness — and you back away from people because you’re feeling overwhelmed. This is natural, but it leads to an increase in loneliness. The top tier is chronic loneliness.

When other people see you’re backing away, they tend to back off too, Nobel said. And the lonely person becomes even lonelier. “It leads to the very high level of loneliness — that’s where loneliness is a serious medical issue,” he said. “So the key isn’t to say, ‘Let’s never be lonely.’ The key is to avoid the spiraling from that base level to middle level to the top.”

The effects of loneliness can run deep. Research shows loneliness increases the risk for depression, anxiety, self-harm and suicide. And breaking out of the spiral gets harder over time.

Reaching out to a counselor or therapist can be an important step in managing the mental health effects of loneliness.

Psychologist Yvonne Thomas, Ph.D., said loneliness lowers self-esteem and feelings of self-worth, which can lead to changes in behavior. “It can make you start lashing out at people, and that can make others not want to be around you … and you’re creating even more loneliness because you’re chasing people away,” she said. “You don’t know you’re doing it — it’s totally subconscious.”

Thomas said loneliness can lead to other destructive patterns, such as substance overuse, sleeping too much and overeating, as a way to avoid reality. “You’re not investing in yourself or you’re not taking good care of yourself, so it can certainly cascade into other problems,” she said.

Nobel noted that women tend to take on more isolating roles, such as family caregiver, that put other people first and allow loneliness to take over.

As noted, anyone can experience loneliness, but research shows that some people are more likely to experience chronic loneliness, including people who:

The symptoms and signs of loneliness vary from person to person but can include:

For kids and teens, parents can look for these common signs that their children may be feeling lonely:

Nobel, who is also the author of “Project UnLonely: Healing Our Crisis of Disconnection,” added that it can be hard for people in caregiver roles to ask for support. If you or someone you know is showing signs of loneliness, there are steps you can take to feel more connected.

Nobel said overcoming loneliness starts by looking inward at your interests and hobbies and what you’re passionate about. From there, he suggests you do some research to see if there’s a club or a group you can join in your area, including faith-based activities if you’re a spiritual person. “It allows you to be in a space or environment of other people who share something. Then it’s easier to disclose things about yourself, which is required in order to connect,” he said.

People who are naturally shy or introverted should take the same approach and look to connect to others through a common interest. “The key is doing something authentic — something you really get a kick out of,” Nobel said. “You can volunteer at a cat shelter, but if you don’t like cats then you’re not going to have this kind of connection through a shared passion for something.”

Many local colleges offer continuing education classes and programs that focus on activities and hobbies like dance, art, foreign language, photography, etc. If you can’t find a group near you, start your own. “It’ll give you even more passion and you’ll feel more enthusiasm again and that can help decrease those negative feelings,” Thomas said.

Read: I’m Turning Anxiety into Art >>

In addition to trying something new, Thomas said to reach out to the healthy relationships with people you have in your life. “You can tell them how you’re feeling, but listen to them too and have a true conversation,” she said. “Maybe they’re going to say they’re lonely too or they’re going through a tough time and you can help them — helping others helps a person feel less lonely.”

If existing healthy relationships are hard to come by, volunteering and fostering are other ways to add connection into your life. “You feel like you’re making a difference and you have a purpose and there is meaning again,” Thomas said.

Working on yourself is also important. Thomas recommended starting the day with 10 or 15 minutes of writing in a journal about two things: A memory where you experienced joy with other people and a time where you felt a connection with somebody. “Write it down so you remember your whole life has not been like this and it doesn’t have to stay like this,” Thomas said.

With so many people living with loneliness, the way forward is putting yourself out there and helping others do the same. “You’re not alone because 50% of people feel significantly lonely from time to time,” Nobel said. “And the other half may not just be willing to say it.”

This educational resource was created with support from Pfizer, a HealthyWomen Corporate Advisory Council member.

Related Articles Around the Web

Ver sangre en tu orina puede ser alarmante, pero podría ocurrir por muchos motivos. Podría ocurrir por tu período menstrual, una infección, problemas con tus riñones o cáncer.

Conoce lo que podría significar si tienes sangre en tu orina si eres una mujer o una persona que tuvo asignación femenina cuando nació (AFAB, por sus siglas en inglés) y qué deberías hacer si eso ocurre.

La palabra hematuria es un término médico para la sangre en la orina. A veces puedes ver sangre en tu orina y puede verse roja, rosada o café. Pero a veces no puedes verla en la sangre y puede detectarse solo con un microscopio o en una muestra de orina. Eso se denomina hematuria microscópica. La hematuria macroscópica es cuando de hecho puedes ver sangre en la orina.

Que haya sangre en la orina no siempre implica que algo está mal, aunque a veces sí. Es importante que avises a tu proveedor de atención médica (HCP, por sus siglas en inglés) para que pueda determinar el motivo.

Aquí encontrarás las 10 razones por las que podrías tener sangre en la orina:

1. Tener tu período menstrual

La sangre durante tu período menstrual sale de tu cuerpo a través de la vagina, así que es común ver sangre cuando usas el baño y esa no es una razón para alarmarse. Pero tu proveedor de atención médica debería evaluar hematurias que ocurren cuando no estás teniendo tu período menstrual, o si ya dejaste de tener períodos menstruales.

2. Infección

Sangre en tu orina puede ser una señal de que tienes una infección de la vejiga, también conocida como una infección urinaria (IU) o una infección renal. Estas infecciones usualmente también causan otros síntomas, tales como una necesidad frecuente o urgente de orinar, dolor pélvico o de la parte inferior de la espalda y orina brumosa y olorosa. Las infecciones renales también pueden causar fiebre, escalofríos y dolor de espalda, en las partes laterales de tu cuerpo o en la entrepierna.

3. Cálculos urinarios

Los cálculos renales, vesicales o ureterales están hechos de sedimentos duros o de cristales de sustancias en tu vía urinaria. Además de sangre en tu orina, los cálculos urinarios pueden causar que la orina huela feo, que sea brumosa, así como dolor intenso en tu espalda o en las partes laterales de tu cuerpo, vómito y fiebre. La mayoría de cálculos urinarios saldrán del cuerpo por su propia cuenta, pero podrían ser muy dolorosos, especialmente si son grandes.

4. Problemas renales

Tus riñones filtran desperdicios y líquidos de tu sangre y producen orina. Cuando los riñones sufren lesiones, podrían permitir que la sangre se filtre en la orina. Una enfermedad renal denominada glomerulonefritis puede causar hematuria microscópica. La única forma para saber si tienes sangre que no puedes ver en tu orina es someterte a una prueba de orina realizada por tu proveedor de atención médica. Si tienes síntomas de glomerulonefritis, tales como hinchazón de tus manos, rostro o pies o una reducción de cuánto orinas, habla con tu proveedor de atención médica acerca de una prueba de orina.

También podrías tener sangre en tu orina si tuviste una lesión en tu riñón, tal como por un accidente o por deportes de contacto.

5. Cáncer

Ver sangre en tu orina podría ser una señal de ciertos tipos de cáncer, tales como cáncer de riñón o de vejiga. Sangre en la orina frecuentemente es la primera señal de cáncer de vejiga y podrían descubrirse rastros durante una prueba de orina. También podrías ver la sangre en tu orina de color rosado o naranja.

6. Problemas de próstata

Si eres una mujer transexual o si tuviste asignación masculina cuando naciste (AMAB, por sus siglas en inglés), sangre en tu orina podría ser una señal de un problema de próstata. Una infección de próstata y una próstata agrandada también puede causar que haya sangre en la orina.

7. Endometriosis

Cuando hay endometriosis, el tejido que normalmente cubre el útero se desarrolla en lugares que no debería. En algunos casos, el tejido endometrial puede desarrollarse en vejigas, riñones o uréteres. Esto puede causar que haya sangre en la orina junto con otros síntomas, tales como períodos menstruales dolorosos, dolor durante relaciones sexuales e infertilidad.

8. Enfermedades hereditarias

La hematuria puede ser un síntoma de anemia drepanocítica o del síndrome de Alport, ambas enfermedades hereditarias. Si sabes que tienes uno de estos trastornos, aun así deberías hacer que se evalúe cualquier tipo de sangre en tu orina para descartar otros motivos.

9. Ejercicio intenso

A veces el ejercicio intenso, deportes de contacto y correr largas distancias puede causar que haya sangre en la orina. En lo que se refiere a los deportes de contacto, esto puede estar relacionado con lesiones de la vejiga o los riñones por recibir golpes. Pero en lo que se refiere a ejercicio intenso o deportes de larga distancia, no se entiende claramente por qué ocurre el sangrado. La hematuria relacionada con el ejercicio usualmente desaparece por su propia cuenta en aproximadamente siete días, pero si notas sangre en tu orina después de hacer ejercicio, también es conveniente que mantengas una consulta con tu proveedor de atención médica.

10. Uso de medicamentos

Ciertos tipos de medicamentos, tales como la penicilina, un fármaco anticáncer llamado ciclofosfamida y medicamentos que previenen coágulos de sangre o que hacen que la sangre sea menos espesa pueden causar que haya sangre en tu orina. La hematuria causada por el uso de medicamentos usualmente desaparece por su propia cuenta una vez que dejas de tomar el medicamento que la ocasionó. Sin embargo, deberías avisar a tu proveedor de atención médica para que pueda determinar la causa de la sangre en tu orina.

Los factores que pueden incrementar tu riesgo de hematuria son, entre otros:

iStock.com/PeterHermesFurian

El tratamiento de sangre en tu orina dependerá de la causa. Por eso es importante avisar a tu proveedor de atención médica si tienes síntomas. A veces, no se necesita ningún tratamiento.

Si tienes una IU o una infección renal, te podrían dar antibióticos para tratar la infección, junto con analgésicos. Podrían prescribirse otros medicamentos para tratar la causa subyacente.

El cáncer puede tratarse con quimioterapia, radiación, inmunoterapia, cirugía o una combinación de estos tratamientos.

Podrías tener tratamientos médicos que son útiles para descomponer los cálculos vesicales o renales, conocidos como litotricia o podrías necesitar una cirugía.

Si tienes sangre en la orina y no estás teniendo tu período menstrual, es importante que visites a tu proveedor de atención médica. Podría realizar una prueba física y hacerte preguntas acerca de tus antecedentes médicos y familiares. Preguntará si tienes otros síntomas, tales como dificultad para orinar, dolor de espalda, náuseas, vómito o fiebre.

Tu proveedor de atención médica podría solicitar una muestra de orina para que se puedan hacer pruebas para determinar si hay sangre en tu orina, especialmente sangre que no puede verse a simple vista. Las pruebas de orina también pueden ser útiles para diagnosticar una infección de vejiga o cálculos renales.

Otras pruebas pueden ser útiles para que tu proveedor de atención médica emita un diagnóstico. Además de revisar tu orina, tu proveedor de atención médica podría solicitar pruebas adicionales, tales como:

Independientemente de la causa, tu proveedor de atención médica podría recomendar consultas de seguimiento para asegurarse que el tratamiento funcionó y que ya no tengas sangre en la orina.

Algunas causas de hematuria son más graves que otras, así que siempre avisa a tu proveedor de atención médica si ves sangre en tu orina. Y reporta cualquier otro síntoma que tengas para que puedas recibir un diagnóstico preciso y un tratamiento inmediatamente.

Este recurso educativo se preparó con el apoyo de Daiichi Sankyo y Merck.

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web

When you get a checkup, or see any healthcare provider (HCP), you may see a physician assistant (PA).

You might be wondering why you’re not seeing a “doctor,” and that’s a good question. PAs are licensed HCPs that work in every medical and surgical setting across the U.S.

PAs can diagnose and treat health conditions, similar to physicians, but most state laws require PAs to work with a physician. This means a physician, a doctor of medicine (M.D.) or a doctor of osteopathic medicine (D.O.) must oversee or supervise patient care with the PA.

Here’s what you need to know about PAs and how they fit into your care team.

Physician assistants are licensed and trained HCPs that deal with patients directly. PAs provide preventive healthcare and can diagnose and treat health conditions and injuries. Overall, PAs have general medical training, which means they can manage a wide range of conditions.

Most PAs work as partners with HCPs in various health-related facilities. These can include:

No. A PA is not a doctor. But PAs can help manage your health and do many of the same things an HCP does. The big difference between PAs and physicians is the amount of time they spend in school and training. A physician assistant degree is a master’s level degree and usually requires around three years of education in addition to an undergraduate degree. Medical school ranges from seven to 12 years after undergraduate school. PAs log fewer hours than physicians overall but still have the education and skills to diagnose and treat health conditions.

The responsibilities of a PA can vary based on a few different factors. The level of experience, state laws and working environment — including the physician working with the PA — can determine what a PA does. Depending on the situation, a PA’s responsibilities can include:

The concept of a PA started back in the 1960s as a way for providers to meet patient demand during physician shortages. Today, many factors contribute to patient demand in addition to a shortage of physicians. The lack of access to quality healthcare is a serious problem for many people in the U.S. — especially for people of color and people who live in rural areas.

This is where PAs can help fill the void and why PAs are in demand. In addition to general medicine, PAs can work with specialists in many different medical fields. These can include:

Yes. PAs can prescribe medication and develop treatment plans based on your healthcare needs. State laws determine what medications PAs can prescribe. For example, PAs in Kentucky can prescribe non-controlled substances but not controlled substances.

Nurse practitioners (NPs) and PAs have similar jobs, but their responsibilities can vary based on many factors, including state laws and training. Both require at least a master’s degree, but NPs are trained to work in specific areas like women’s health or pediatrics. PAs are trained using a medical model, similar to physicians, to deal with more general health conditions. Also, most NPs in the U.S. can see patients without working with a physician, but most PAs have to work with a physician in order to practice medicine.

Think of a PA as your go-to person for the healthcare support you need, just like a physician. PAs can manage your treatment plan, prescribe and refill medications, and keep track of your overall well-being and health. In many cases, you will only see your PA, who will work with a physician to maintain a healthcare plan that works for you. PAs can also connect you to other HCPs if you need a specialist.

Bottom line: PAs are HCPs that can diagnose and treat conditions.

This educational resource was created with support from Pfizer, a HealthyWomen Corporate Advisory Council member.

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web

As told to Jacquelyne Froeber

February 21, 2025, is National Caregivers Day.

My dad was the fun parent.

Growing up, we did pretty much everything together, but Saturday mornings were my favorite. Dad would turn on the radio and blast the bluegrass music he loved while we tossed a softball in the side yard.

Dad was the one who taught me how to throw a proper pitch — and really all the important things you need to know as a kid. (No offense to my mom — she was amazing — but dad just had a light inside him.)

Everyone liked my dad. He was an auditor with the state IRS, and still people were genuinely happy to see him — that’s how likeable he was. You couldn’t help but smile when he was around.

When I was a teenager, my dad drove me everywhere and picked me up from school most days of the week. But one afternoon, he just didn’t show up.

“He must have gotten stuck at work,” I thought.

When he got home, he apologized — he completely forgot to pick me up. Which, as a selfish teen, really shocked me. But then I started noticing that other things were off, too. He had a funny smell that I couldn’t place. Dad was a big drinker, so maybe now he was day drinking? He’d also started flapping his hands at random times. I was mortified by this new quirk, so I tried to blame alcohol for that too. And, of course, for the forgetting.

A few weeks after dad forgot to pick me up from school, he couldn’t remember how to get home from the building he’d worked in for almost 23 years. That’s when we knew something was very wrong.

We knew Dad had cirrhosis of the liver — a chronic liver disease — from drinking too much. There was a lot of shame and stigma surrounding that diagnosis, so we had all just silently agreed not to talk about it. But we thought whatever was going on now must be something else entirely.

We never imagined these new behaviors had anything to do with his liver disease. So when we got him back to his doctor and he told us that dad had overt hepatic encephalopathy — that his liver disease had progressed and was now affecting his brain — my mom and I were stunned. Progressed? We didn’t know that was possible. We didn’t know his cirrhosis could ever affect his brain.

But it turned out toxins from the liver disease were building up in his bloodstream, and that buildup was causing brain damage. The forgetfulness, the smell, the involuntary movements — all of it was hepatic encephalopathy. And it only got worse from there.

As the shock of the diagnosis wore off, the guilt and sadness sank in. My mom and I felt terrible, like we could have helped him, we could have gotten him back to the doctor sooner if we’d known that we were experiencing a progression. We would have been more vigilant if someone had told us to look out for any changes in him and report back. I felt like a failure as a daughter.

We didn’t have much time with dad after the diagnosis.

For decades, I carried around the shame that I hadn’t been able to help my dad when he had hepatic encephalopathy. I didn’t talk about it with anyone. But recently, I started seeing more about the condition online, and I learned that treatments had progressed and that communities of patients and caregivers were forming. For the first time, I felt like sharing my story because I never want anyone to feel as alone or ashamed as I did for so long.

Last year, I joined the “I Wish I Knew” campaign that helps caregivers and patients learn about the risks and symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy. Caregiving is a crucial part of diagnosing and managing symptoms, and thinking back to how little my mom and I knew while caring for my dad made me want to help out in any way I could.

Through the campaign, I’ve been honored to talk with different caregivers about their experiences and post our conversations on social media to raise awareness about hepatic encephalopathy. It continues to mean so much to me to get to share these stories.

The conversations are also an important reminder to practice self-care as a caregiver because when you’re trying to care for someone you love you often forget to care about yourself. And when your well runs dry, there’s nothing left to give. It’s vital to ask for help when you need it, and it’s beautiful to take the initiative to offer help when you have the strength to.

For people supporting caregivers, that can look like saying, “I can watch your kids for a bit while you go into the other room and have a good cry.” Or showing up with lasagna for dinner. Any little act of love aggregates like raindrops in an ocean.

If you know someone who’s been diagnosed with any sort of liver disease, know that it’s a journey. Your diagnosis is not your destination. It’s important to educate yourself about what the symptoms might be, what progression can look like and what might be on your horizon. Just knowing what to look for will help you catch any changes as soon as they’re happening. But also know that not everything happens to everyone: Your journey will be unique. The most important thing is to love each other through it as best you can.

Looking back, I think coping is about radical acceptance. You can’t pretend the disease isn’t happening or that it will go away. If you really start where you stand and accept the moment you’re in, then you can meet that moment with your full heart. My family and I lived so many years in denial and shame. It didn’t serve my dad — and it didn’t serve us.

For caregivers today, there’s so much community. And the more we bring the disease into the light and we bring each other together — that’s when we really can face this with all our might.

Perhaps the most important thing my dad ever taught me was the power of positivity and joy. Now when my well is depleted, I know I can turn to my community: I know they hold my stories and my heart. Somehow, when I’m with them, I can feel my dad smiling. And I can smile too.

Have your own Real Women, Real Stories you want to share? Let us know.

Our Real Women, Real Stories are the authentic experiences of real-life women. The views, opinions and experiences shared in these stories are not endorsed by HealthyWomen and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of HealthyWomen.